This article was first published in The Conversation on 18 July 2011 under the title “From scraping by to pizza and pie: how protein price drives obesity”. It is based on part of the argument in Chapter 2 of Sex, Genes & Rock ‘n’ Roll: How Evolution has Shaped the Modern World

For the first time ever, the number of overweight people on Earth outweighs the number that are undernourished.

From the obesity crisis flows a cascade of health and social problems: it burdens healthcare services, hobbles workforces and ruins lives. Yet despite its tragic importance, we still don’t fully understand the causes of the obesity crisis. Energy-dense foods are definitely part of the problem though.

Pizza and French fries contain twice the energy of lean meat, and ten times as much energy as broccoli.

Tackling the obesity crisis requires us to reverse the rising tide of energy-dense take-away and pre-prepared foods, substituting them with simpler old-fashioned foods, such as meat and veggies.

But why do we scoff these energy-dense foods in the first place? Well, perhaps because they are more affordable. A consumer gets more kilojoule for their buck from chips and pizza than from broccoli and lean meat – why spend more on healthy foods when pizza or chips are cheaper (and tastier)?

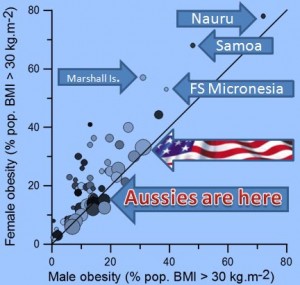

We tend to think of obesity as a side-effect of Western opulence. It isn’t: the seven countries with the highest obesity rates are all relatively poor Pacific island nations (see the graph). And in wealthy nations the obese are far more likely to be poor than wealthy. The rich can afford to eat well, but poor people are trapped into eating unhealthy energy-dense foods.

Protein vs. carbs

The link between food prices and obesity gets stronger when we consider the price of protein. Our bodies need protein in order to grow and repair. That protein comes from our diet and cannot be stored, so we need to eat enough protein each day to meet our needs.

Professor Steve Simpson of Sydney University, together with David Raubenheimer of Massey University in New Zealand, points out that the amount of protein we eat each day has an enormous effect on how much we eat overall.

According to their research, at least 14% of our dietary energy should come from protein and if our diet contains too little protein, we eat extra carbs and fat to compensate.

Simpson and Raubenheimer’s “Protein Leverage Hypothesis” explains why we feel so full after a meat-heavy Christmas or Thanksgiving dinner, and why, if we don’t meet our daily protein needs, we eat enormous amounts of extra carbohydrate and fat to compensate.

Perhaps the rising cost of protein relative to carbohydrates and fats might explain the explosion in obesity. In collaboration with Simpson and Raubenheimer, I confirmed this prediction by doing a quick trip to online supermarkets in Sydney and Seattle.

It turns out that each megajoule (MJ) of energy in a food item raises the price of that item by an average of US17¢, but the effects of carbohydrates, fats and protein on food price could not be more different.

Each MJ of protein within a food item raises the cost of that item by US$3.26. Surprisingly, each MJ of carbohydrate actually reduces the cost of a food by US38¢. So, it’s getting cheaper to get the energy we need to stay alive, but more expensive to meet our protein needs and thus satisfy our appetites.

Consumers on a tight budget find themselves buying bigger quantities of sugary and starchy foods and smaller amounts of expensive high-protein foods such as dairy, fish, meat and fresh vegetables.

The average westerner today consumes about 15% more energy than they would have in 1970. Interestingly, it would cost less than US72¢ cents a day for a person to cut their energy consumption by 15% by switching from a carbohydrate-rich diet to more protein-packed foods including lean meats, fish and, unfortunately, lentils.

This works out at a saving of $262 per person per year, or less than one fifth the cost of extra medical care that each obese person needs. It appears that switching to more protein-rich foods would be a highly cost-effective intervention in terms of the medical costs of obesity alone.

Empty carbohydrates

Nutritionists often describe sugary drinks and snacks as “empty carbohydrates”, but “cheap carbs” might be a better description.

For most of human history, our hunter-gatherer ancestors relied on lean meat and high-fibre plant foods. Agriculture, which first began no more than 12,000 years ago, introduced starchy carbohydrates such wheat, rice and corn into our diet.

Since then, carbohydrates have become increasingly plentiful – due to simple market forces – as well as cheaper.

Since the 18th century, sugar has rocketed from a rare delicacy to a major source of dietary energy, propelled first by industrialisation and slavery in the Caribbean sugar colonies, and then by continuous increases in the efficiency with which sugar cane can be farmed, cut and processed.

The great 18th century economist Adam Smith witnessed the start of these changes and the harm they did, as sugar and the rum that was distilled from Carribean sugar began to flood the European market.

In 1776, he wrote in The Wealth of Nations:

“Sugar, rum, and tobacco are commodities which are nowhere necessaries of life, which are become objects of almost universal consumption, and which are therefore extremely proper subjects of taxation”.

Enlightened societies now recognise the enormous social and healthcare costs associated with alcohol and tobacco use. Via taxes and the awards of legal damages, those societies now push some of those costs back onto the suppliers.

I can’t imagine governments will easily remove the tariffs and subsidies that make sugar prices artificially cheap. But perhaps they will tax the sugary, starchy and fatty products that cause such harm.

People most at risk of obesity tend to be heavy consumers of soft drinks, cordials, fried potato products and ice cream – foods that are full of sugar, starch and (sometimes) fat. Importantly, such products contain very little protein.

Taxing products like these might be a helpful first step. In fact some American states – such Maryland and Virginia – have already enacted substantial taxes of high-sugar drinks, causing consumption to plummet.

New York’s mayor, Michael Bloomberg, infuriated civil liberties groups and the sugar and soda lobbies last October when he asked the US Department of Agriculture to allow New York City to ban the 1.7 million citizens who receive food stamps from using them to buy soda.

Those Americans poor enough to receive food stamps are precisely the people most at risk of obesity: people with enough access to food that they do not starve, but not enough money to eat a healthy diet with plenty of protein.

So did Mayor Bloomberg have the right idea? Should we tell people what they can and can’t eat or drink? Libertarians love to tell us that we have a choice, and that nobody is forced to overeat.

Hopefully by recognising how ancient, evolved biology combines with modern economics, we’ll be able to move beyond arguments about choice and blaming the people whose circumstances lead them toward obesity.

______________________________________________________________________________________

Postscript: The evolutionary economist Jason Collins, after reading my book and considering my arguments regarding obesity and economics, posted this article on his excellent blog Evolving Economics. He raises good concerns about a sugar tax or any of the other interventions I suggest or hint at, and there is more thoughtful discussion int he comments after his post.

One Reply to “Why poor people in wealthy countries are at greatest obesity risk”