A shorter version of this article first appeared in the Sydney Morning Herald and other Fairfax publications on 14 February 2012 under the headline “The true course of love was never about profit“.

Valentine’s day. What’s not to love about overpriced roses, overbooked restaurants and overstuffed soft toys? It’s the day we render the most multifaceted and untameable of human passions as flat and commercialised as a Kardashian marriage.

Okay, so I’m not so hot on Valentine’s day. Perhaps that’s not surprising for a scientist who studies sexual conflict, the intriguing but somewhat depressing idea that male and female evolutionary interests can never, exactly, coincide.

Early evolutionists took a typically Victorian view of sex: hasty, prudish and patriotic. Lie back and think of England. Do it for the Queen, the Empire, or the perpetuation of the species. Even today our nature documentaries talk about animal sex as though it were a benign tea-party. But sex in the animal world is far messier, more complicated and infinitely more interesting than most people realise.

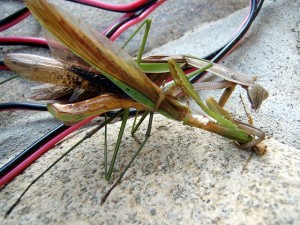

Some female spiders and insects take a notoriously oral approach to sex – dismembering and consuming the hapless little male. Seed beetle penises resemble tools of mediaeval torture that inflict internal damage on the female. The female’s pain is the male’s evolutionary gain as the unwholesome experience dissuades her from mating again with another male. Anywhere you turn in the animal world, what’s good for the goose is seldom also good for the gander.

Human coupling and relationships, too, seethe with conflict. We disagree over when to start having sex, how often to have it, and how quickly to fall asleep afterwards. Couples differ on when to have children, how many to have, and who is going to get up in the night when the screaming starts. Economists model the simmering tensions about who does what household jobs, how much money the family needs and how to spend it. And many couples play chicken over whether to stay together, who is going to leave first, and who will take the children.

If all of this is too dark and unfamiliar to you, that is because only a small fraction of these ever-present conflicts breach the surface of our conscious awareness; most relationships feel happy most of the time. But the conflict between our interests, even within the most loving couples, means that people only manage to get together and raise children courtesy of a most remarkable evolutionary adaptation: romantic love.

Tina Turner called it a second-hand emotion, but according to anthropologist and author Helen Fisher it isn’t even an emotion at all: “It’s a motivation system, it’s a drive, it’s part of the reward system of the brain.” Love is so many-splendoured because it does so many jobs. At least six different hormones signal to several dozen different tissues and organs at various times in our romantic lives, arousing us to crave sex, attracting us to healthy and high quality mates, bonding us to our beloved, and all the time helping us to thwart the conflict between us and focus on our common interests – including the difficult business of raising a healthy child.

The first flush of obsessive-addictive love comes courtesy of a spike in dopamine and a dangerous drop in serotonin. Dopamine – the addictive part – causes the euphoria of falling in love and of orgasm. Those pleasant feelings evolved to reward us when we do what is good for our genes. Little surprise, then, that once we acquire a taste for that special somebody, or for sex in general, we want to keep on coming back.

Low serotonin causes the obsession. Normally we need high levels of serotonin to feel well. Anxiety, depression and obsessive-compulsive disorders come, at least in part, from a lack of circulating serotonin. So when we fall in love we surrender to natural obsession – but thanks to the dopamine spike it’s mostly a happy obsession.

Other hormones cut in later in our relationships. Long-haul bonding and commitment, and the desire to cuddle up and reinforce those bonds with a spouse or long-term partner come courtesy of the hormones oxytocin and vasopressin. At every stage of romance’s course our bodies mix the cocktail of hormones that best motivates, drives and rewards us given our current circumstances.

You may find this all unromantically reductionist. I beg to differ. It’s certainly no less romantic than the sugar-coated, sanitised view that infiltrates shops at this time of year, between Christmas presents and Easter eggs. That hormonal alchemy of intimacy, trust and infatuation does something more remarkable than any rom-com plot. It tricks us into putting aside our very justifiable fear of unrelated people, and enmeshing our reproductive future with somebody else’s. And then it keeps on tricking us into staying together.

And so we triumph – even if imperfectly and impermanently – over sexual conflict. That is the true and awesome power of love.

One Reply to “The true power of love – how we triumph over sexual conflict”