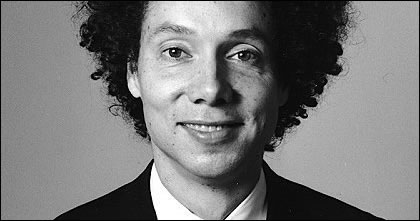

Hasn’t Malcolm Gladwell had a busy fortnight? His latest book, David and Goliath: Underdogs, Misfits and the Art of Battling Giants, shipped on the first of October. And the deluge of reviews washed out a flood of anti-Gladwell bile. He’s an unusually polarising author, Gladwell. And it looks like some of the criticism has stung.

The idea animating Gladwell’s David and Goliath is the old paradox that our greatest strengths can also be the source of our weakness. And that difficulties and disadvantages, from childhood poverty to dyslexia, can form the crucial ingredient in success.

But what propels the book, like all of Gladwell’s writing, is his intoxicating brand of storytelling. He is the master of mixing familiar elements with surprise counter-intuitions, and then seasoning with a sprinkling of scientific evidence. Here he ruminates on the familiar Old Testament tale from which his book derives its title:

Nobody contests that Gladwell writes compelling, readable books. Books like Blink, Outliers and The Tipping Point that make vast numbers of readers feel smarter, and spawn memetic ideas about the world and how it really works. Any non-fiction author, invited to meet the devil at the crossroads, would open negotiations with a fraction of Gladwell’s sales and influence as a target.

But that awesome strength in narrative story-telling and character-driven non-fiction turns out, in the eyes of many critics, to be Gladwell’s weakness, too. Those critics – many of them scientists, lesser-known authors, and commonly both – consider Gladwell’s too willing to compromise about the “non” in non-fiction. To critics, he seems to take a rather one-eyed view of the scientific evidence: happy to garnish his writing with citations of research that suits his argument. He’s not renowned for exploring nuance, complexity or even evidence that flat-out contradicts his thesis.

Psychologist Christopher Chabris seems to have got under Gladwell’s skin with a multi-barrel onslaught on David and Goliath.

- First, there was the review in the Wall Street Journal, in which he argues “Malcolm Gladwell too often presents as proven laws what are just intriguing possibilities and musings about human behavior”.

- Chabris had so much material lined up that he blogged a week later under the heading Why Malcolm Gladwell Matters (And Why That’s Unfortunate).

- Chabris re-treaded that piece for Slate, accusing Gladwell of deliberately misrepresenting the science.

Three attacks in little over a week irritated Gladwell into a response, again at Slate (Christopher Chabris Should Calm Down). Rather than tackle Chabris’ accusations of misrepresentation on their own terms, Gladwell suggests that Chabris lacks sufficient appreciation of the narrative form.

Chabris should calm down. I was simply saying that all writing about social science need not be presented with the formality and precision of the academic world. There is a place for storytelling, in all of its messiness. My point was that the people who read my books appreciate this. They are perfectly aware of the strengths and weakness of the narrative form. They know what a story can and can’t do, and they understand that narratives sometimes begin in one place and end in another.

Gladwell points out that Chabris has been gunning for him since about the time Chabris and Donald Simons published The Invisible Gorilla: How our Intuitions Deceive Us. Beginning with a piece in which they attacked Gladwell’s Blink. He reveals evidence of a Gladwell obsession in the Chabris household, highlighting an article entitled “Malcolm Gladwell is a Bullshitter”, by Michelle N. Meyer, the wife of Professor Chabris.

Gladwell is too clever to say so directly, but I drew from his self-defence the implication that Chabris’ criticisms are those of a jealous, lesser author. Perhaps one picking a fight with a publishing Goliath in order to boost his own sales and reputation. Even Gladwell’s gracious concession to admire the science that Chabris does implies that Chabris’ strong suit is in doing the science, rather than writing about it.

It all makes for a delectable spat between authors. Not quite as pompous as the famous enmity between Richard Dawkins and the late Stephen Jay Gould (brilliantly covered by philosopher Kim Sterelny), but every bit as entertaining. I hope it will be as illuminating.

Is there a place for Malcolm Gladwell?

Gladwell’s writing isn’t much to my taste. I abandoned Outliers about three pages in, my senses flooded by lyrically-rendered minutiae of sandstone stairs and slate mines in the twin settlements of Roseto, Italy and Roseto, Pennsylvania. But I’m also happy to acknowledge that Gladwell is a master craftsman, an outlier among authors. And if I want to sell more than a few thousand copies of my next book, I realise I could do far worse than attempt to emulate what he does so well.

But I share with Chabris and the sizable anti-Gladwell mob a frustration that Gladwell’s writing over-smooths the messy, difficult world we all seek to understand. And it under-sells the two-steps-forward-one-step-back complexity of real science.

The wonderful term ‘over-smooth’ comes from Andrew Gelman, in the best article I have yet seen on the Gladwell-Chabris spat:

Here’s the problem. What Chabris is saying (I think)—and, in any case, what I’m saying—is that the messiness of reality is a key way that stories work in conveying information and overturning our preconceptions.

When I wrote that some of Gladwell’s stories are over-smoothed, my problem was not that Gladwell was not academic, or that he had too much messy reality in his books. Rather, my problem (and, I think, Chabris’s as well) was that Gladwell’s stories were not messy enough! Fables are fun, but the real world can be much more interesting.

In the end, I’m pleased that authors like Gladwell write, and enjoy a wide readership. Their books stimulate plenty of genuine thought, and they build third-culture links between artful storytelling and real science.

They certainly trump the vast majority of books shelved under non-fiction in the book stores I visit. Most of which range from useless to downright harmful: any kind of management handbook, the vast majority of diet books and nearly all relationship claptrap. And that’s before we encounter the stuff that only gets filed under non-fiction through mischievous irony: The Secret, any book with Mars and Venus in the title, and the entire oeuvre of Deepak Chopra.

I’m glad people are reading Gladwell, rather than complete rubbish. But readers are smart and they deserve a chance to read the most genuine and honest attempts to interpret the world as it actually is. Gladwell, himself, describes his work as a ‘gateway drug’ – an entree to the real popular science. I’d love to know if Gladwellian non-fiction that dominates New York Times bestseller lists, all character-driven and bristling with narrative style, actually builds the market for more serious, less over-smoothed authors. I tend to side with authors who think a dollar spent on a Gladwell book is a dollar not spent on theirs.

Just as I’m glad there are people who read Gladwell instead of garbage, I’m equally grateful to folks like Chabris and Gelman who yap at the heels of authors and keep them honest. Non-fiction authors have a duty to try not to be wrong.

But one of my own guiding principles is a quote from the great ecologist Bob MacArthur:

There are many worse things than being wrong. One is to be trivial.

Like him or not, Malcolm Gladwell is decidedly non-trivial. But, as Gelman suggests, he could do us all a favour by loosening up:

Try resisting the urge to tie every story into a bow. Let some of the loose ends hang out. I think that’s what Chabris is trying to say.

Like, love or loathe Gladwell? Let me know why in the comments or on Twitter (@Brooks_Rob)

Rob Brooks does not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has no relevant affiliations.

![]()

This article was originally published at The Conversation.

Read the original article.

One Reply to “Gladwell and Goilath: When Great Strength Becomes a Weakness”