Are you a feminist?

It’s a question I ask of my third-year Animal Behaviour class every year. I ask the question in a lecture, near the end of the course, about human sexuality. It’s a part of the lecture where I discuss sexual conflict: the idea that what’s best for one mate isn’t necessarily best for the other.

This leads on to discussion about how sources of power (such as the work women and men can do in a society), and customs that shape the supply and demand of sex can dramatically change human mating patterns. It’s one of those areas where evolutionary biology offers remarkable, powerful insights into difficult political and ideological issues.

I’m always surprised at how few students answer in the affirmative. Last week, when I asked the question, just two students raised their hands. And rather sheepishly, at that.

Many probably equivocated and held back, reluctant to take a position in front of their classmates. Others have probably not really thought about it that much. And others, sympathetic to ideas of equity have been turned off the idea by negative stereotypes of feminism.

Whether or not to identify with feminism, or as a feminist, has never, it seems, been quite as complicated as it is today. Why wouldn’t it be? Hear the words of one of 2013’s most influential women, Beyoncé, this very week playing to packed Australian arenas.

I truly believe that women should be financially independent from their men. And let’s face it, money gives men the power to run the show. It gives men the power to define value. They define what’s sexy. And men define what’s feminine. It’s ridiculous.

The ridiculously confusing bit (something we used to call irony before the hipsters thought it was cool), as Hadley Freeman pointed out in The Guardian earlier this year, is that Beyoncé shares this wisdom in American GQ:

A men’s magazine in which she poses nearly naked in seven photos, including one on the cover in which she is wearing a pair of tiny knickers and a man’s shirt so cropped that her breasts are visible.

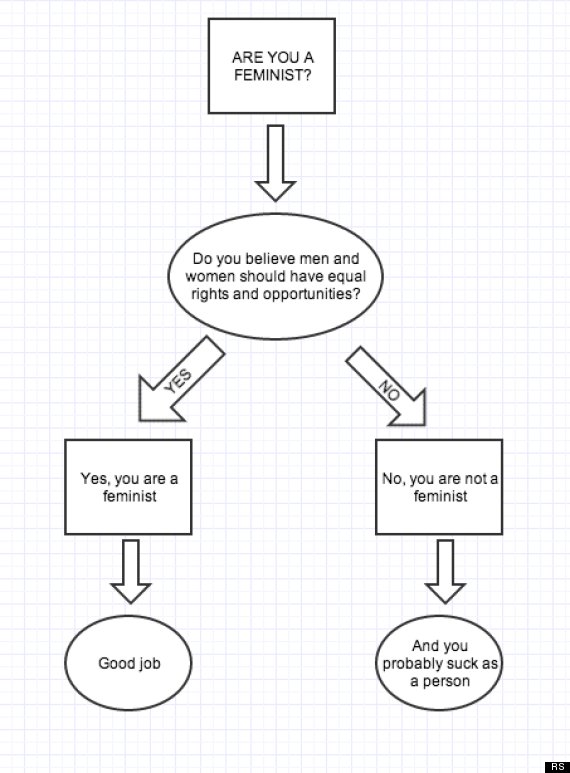

Ruminating this weekend over why so few of my smart, engaged students would self-identify as feminists, I was delighted to see this flow-chart in an article by Rebecca Searles, an editor at Huffington Post.

Uncomplicating feminism

Rebecca’s flow-chart is, of course, a massive oversimplification. With a delectable bit of polemicism thrown in: if you aren’t in favour of equal rights and opportunities then “you probably suck as a person”. It probably won’t become the new litmus-test for a suddenly unified global feminism. But she makes a valuable point that, in a world where rights and opportunities are far from equal, those in favour of equality, or equity, should seek to find and identify with one another.

Searles designed the flow-chart in exasperation at contemporary pop-stars and teen role models who misuse the term “feminist”, thus both undermining feminism and sounding “like idiots”.

If you’ve read this column, or my book, you’ll have a fair idea of my politics. Many of my favourite commentators on this site call me a feminist, thinking it’s a perjorative term. Which makes them sound, as Rebecca Searles might say, “like idiots”. But forced to label myself, I’d call myself pro-feminist.

Why so reluctant to call myself a feminist? As a man, I’ve always felt it safest to stay outside the tent, happy for the title to be conferred from within but reluctant to claim it for myself.

It’s a position reinforced earlier this year with the spectacular fall from grace of Hugo Schwyzer, the internet’s erstwhile highest profile male feminist. Schwyzer rather dramatically quit the internet (how is that even possible?), twice, when his troubled personal history and a recent affair caused a rather spectacular swing against him in his own constituency [I’ve collated some of the key links here].

There is inherent peril, I feel, for a man who leans too heavily on his feminist credentials. Some, like Schwyzer, have Tyrannosaur-like skeletons in their closets. All of us have the inevitable flaws to which human flesh is heir.

I’m not the only one for whom the word “feminist” conjures an exclusively feminine image. Consider the hilarious Caitlin Moran. In her recent book How to be a Woman, Moran first laments the same confusion among women over whether to identify as feminists:

We need to reclaim the word ‘feminism’. We need the word ‘feminism’ back real bad. When statistics come in saying that only 29% of American women would describe themselves as feminist – and only 42% of British women – I used to think, What do you think feminism IS, ladies? What part of ‘liberation for women’ is not for you? Is it freedom to vote? The right not to be owned by the man you marry? The campaign for equal pay? ‘Vogue’ by Madonna? Jeans? Did all that good shit GET ON YOUR NERVES? Or were you just DRUNK AT THE TIME OF THE SURVEY?

Moran then offers what, after Searles’ flow-chart, must be the second most pithy test for the question “Am I a feminist?”

So here is the quick way of working out if you’re a feminist. Put your hand in your pants.

a) Do you have a vagina? and b) Do you want to be in charge of it?

If you said ‘yes’ to both, then congratulations! You’re a feminist.

Moran’s book is, of course, about How to be a Woman – it says so in the title. She writes for the Beyoncés and the Katy Perrys, and more particularly for the women who revere them and think that Keeping up with the Kardashians might be a pretty neat idea. She’s not offering serious “am I a feminist?” advice to academic men who understand that equitable societies are the best kind to live in.

But Moran’s rather anatomic test reinforces my concerns about whether a man can ever claim to be a feminist in the same rock-solid way a woman can. Even though I’m entirely clear on the importance of feminism and of equity.

But it does seem clear to me that the question “am I a feminist?” should be a simple one for any woman to answer, irrespective of whether they use Searles’ method or Moran’s.

Rob Brooks does not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has no relevant affiliations.

![]()

This article was originally published at The Conversation.

Read the original article.